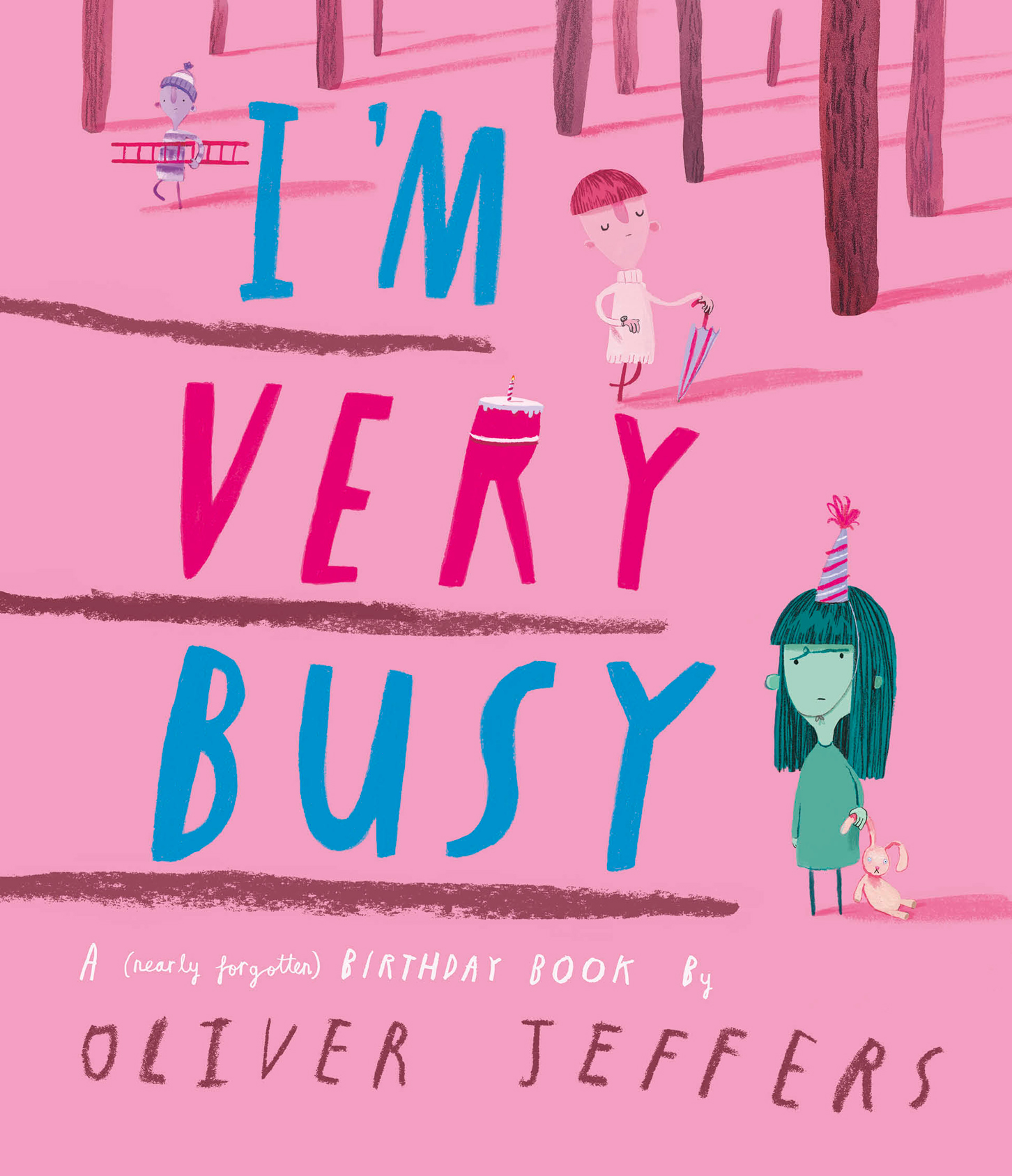

Oliver Jeffers was born in Port Hedland, Western Australia, and raised in Northern Ireland. His paintings have been exhibited worldwide and his picture books for children have been translated into more than 30 languages. His second book, Lost and Found, was developed into an animated short film, which received more than 60 awards, including a BAFTA for Best Animated Short Film, and We Are: Notes for Living on Planet Earth has been adapted to a short film by Apple TV+.

In his Letter to My Younger Self, Oliver Jeffers recalls what life was like during The Troubles, his relationship with his parents and returning to live in Northern Ireland.

When I was 16 I knew I wanted to try and get into art college. So art was a fairly big preoccupation. I think I was also very interested in playing football on the street. I was maybe starting to get out of my tree-climbing days around then. I remember reading the news and being aware of things that were happening in the world, but not really having an opinion on them, and being a bit worried by that, not knowing who I really was. My dad told me everybody becomes themselves at a certain point, it’s OK to be closed for renovation for a time. I wasn’t a rebellious teenager, because my mum was very ill. She had MS, so we had to look after her a lot. I didn’t even really drink or anything like that until my mid-20s. I was a late bloomer. So it was a fairly innocent childhood, but I was constantly in awe of how big and how wide the world seemed.

Life in Northern Ireland during The Troubles was kind of normalised in the sense that you just get on with your life. But there’s all kinds of undocumented trauma that people are carrying around with them, and you see it manifest in various ways. For example, I would never sit with my back to the door in restaurants, even in a different country. Also I realised that at a certain point I stopped watching any films or documentaries about The Troubles. They were just too triggering. We used to say we were bilingual because we could speak both Catholic and Protestant. You knew what to say if you were walking through the wrong neighbourhood. So it was a lot to bear.

I had a fantastic relationship with both of my parents. My mum was a troublemaker when she was small, but for the last 30 years of her life, so most of the life that I remember, she was wheelchair-bound and then bed-bound for the last decade. MS eventually took her life in the year 2000. But she always encouraged me to travel and to get away from Belfast and understand it from a new perspective. My dad, I still talk to him almost every day. He just lives behind us, and we often call round. He was a teacher and very, very encouraging of an art career when that was not normal to do. It took bravery to let me pursue what I wanted rather than what was conceived to be a real job.

I think my younger self would be surprised at how far you can actually get with just being able to draw simple pictures and understand how people feel, and try and convey it in a way that others understand. I remember thinking I would love to be an artist when I grew up, but thinking I should probably prepare for a real job. I think the young me would be very, very proud of how it’s worked out. I think a large part of it is that I can still remember the way I thought about the world at the age of six and 16 and 26, and I was able to tap into some of that naivety, some of that whimsy, and turn it into a story.