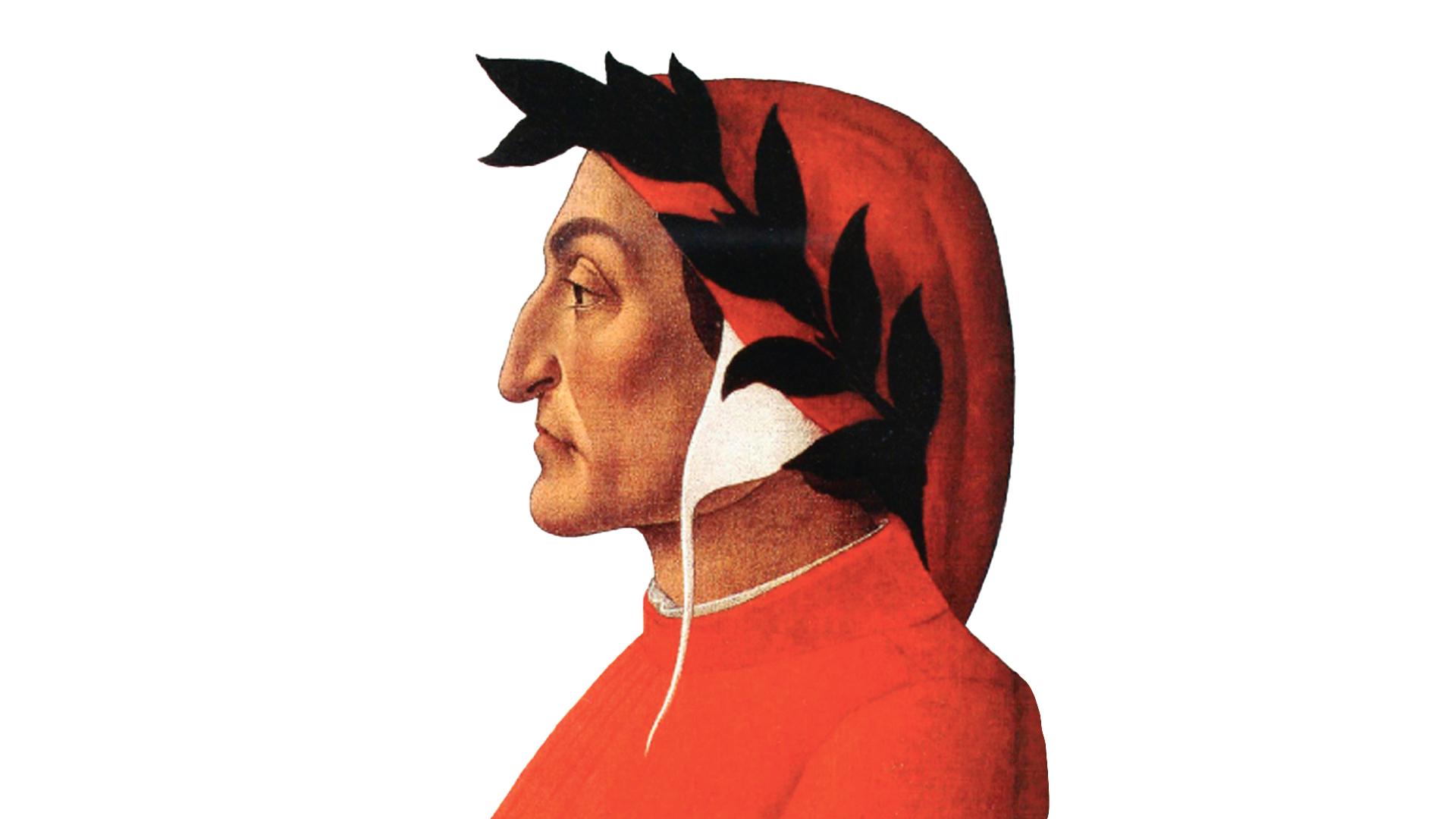

Dante Alighieri: poet, philosopher and potentially the pettiest man in all of 14th-century Italy. Which is, to be clear, meant entirely as a compliment.

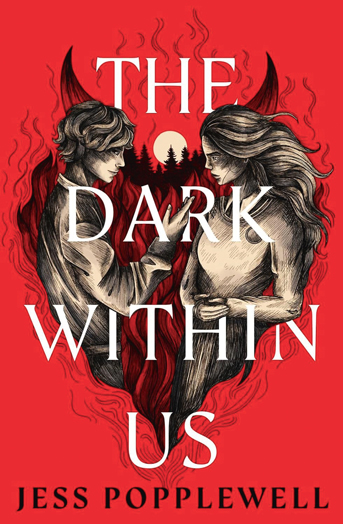

If you’re not familiar with the name, and don’t know why anyone might be discussing a medieval poet’s levels of petty, let me introduce you: Dante (as he’s most commonly known – you know, like Beyoncé, or Cher), wrote a narrative poem made up of three sections – ‘Inferno’ (hell), ‘Purgatorio’ (purgatory) and ‘Paradiso’ (heaven), collectively known as The Divine Comedy. These poems are still famous today, partly because they have inspired loads of other cultural depictions of the afterlife since they were written – most recently, my book, The Dark Within Us, in which a modern teenager descends into Dante’s version of Hell.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

So, why do I call Dante petty? Well, in The Divine Comedy, he tells the story of himself as he heads on a walk through the afterlife. As he passes through Hell, Dante meets a host of sinners – some of whom were real people, living contemporaries, who he had some kind of grudge with. A grudge that led him to immortalise them, suffering in the flames of Hell. Which is, I hope we can all agree, petty behaviour.

And look, I only like drama I’m not involved in personally, so a gothy account of the gossip from 14th century Florence? Sign me right up. Thankfully, the copy of Inferno I read as a 16-year-old included lots of study guides and footnotes, helpfully explaining who the Black Guelphs were, and why Dante was mad at the Pope. Imagine that – your personal grievances are still going strong almost 700 years on. You can see why he’s a literary icon.

- The loss of humanities courses like English literature will leave education in a poorer place

- How letters from a 15th-century housewife unlock secrets of a forgotten England

At around the same time I first read Inferno, I decided I wanted to write a book, and although I didn’t really recognise it at the time, Inferno inspired me in more ways than just being a cool setting. For example, Dante wrote himself into his narrative. He was braver than me about it – the character in The Divine Comedy is literally called Dante, while I merely took inspiration from my life to invent my main character, Jenny. You see, as well as reading Inferno when I was 16, I also ran away from home, a decision that led to several years of sofa-surfing or otherwise insecure accommodation. So, you could argue that Jenny is a version of me – albeit much cooler and clearer-headed than I ever was. She begins the book sofa-surfing on her auntie’s couch, after a targeted cyber-bullying campaign leads her to fall out with her mum.