No one at work knew my home life was so volatile. I was ambitious and upbeat. Deep down I sensed that the man who had always said “the world is your oyster!” would not object to me pursuing happiness, even if I had to let him go to keep the possibility alive.

Shortly after I left for Australia, my dad emailed to let me know that my grandad had died. I replied, then we weren’t in touch until I wrote to him a final time in the autumn before he died. My sister gave him a printout of my email. By then our dad was living in a hostel with no phone or laptop. Every day I keep in mind all that you taught me, I wrote, I hope you’re finding ways to be well and see the beauty too. “See the beauty” was one of his refrains during my childhood.

Read more:

I began writing my book the day after he died. I felt compelled to record our time together and apart – for the grandkids who’d never get to meet him, for everyone who loves an addict, for my dad who had raised me so lovingly, and for myself who had forged a way out of the spiralling chaos.

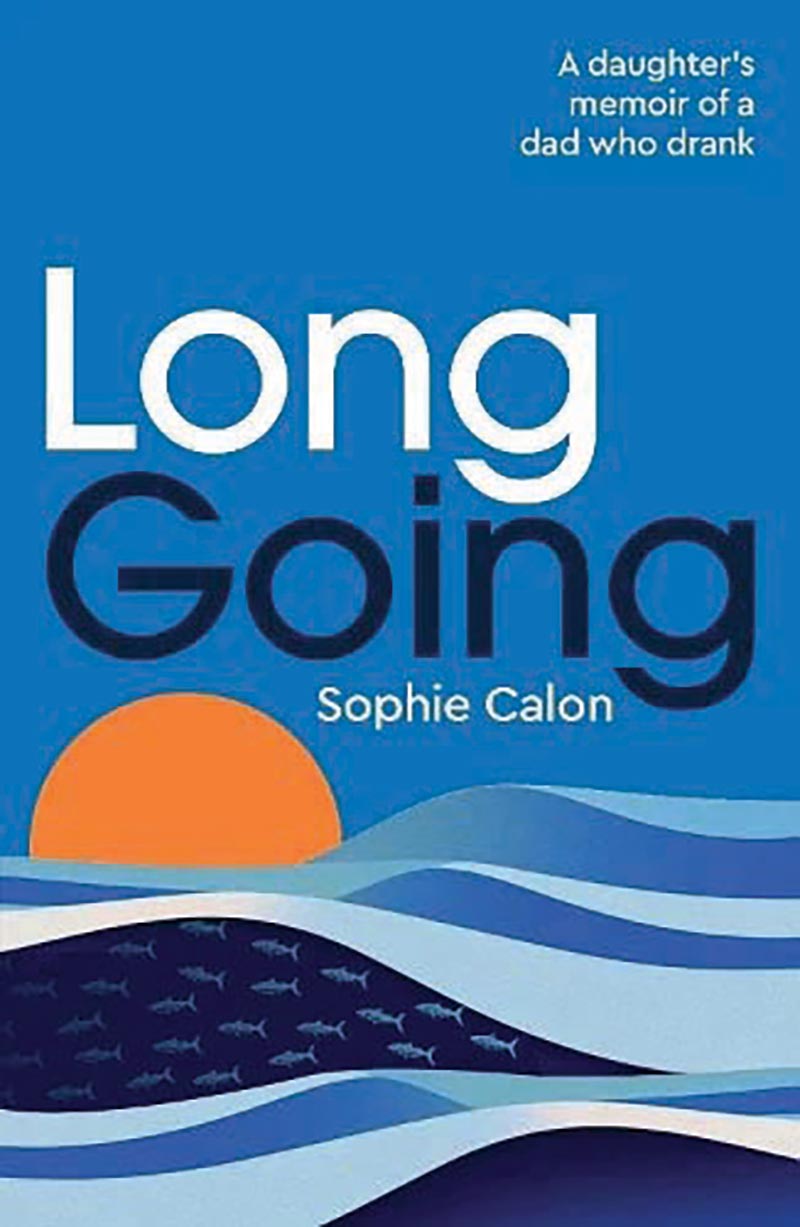

This summer, Honno published my memoir Long Going and I feel closer to my dad than ever before. In writing the book, I revisited hundreds of our emails and letters, as well as my dad’s notes from his stints in prison and homeless shelters. Looking back I neither blamed him nor let him off the hook, as one review noted. My dad was only human, after all.

For many, estrangement is still a source of shame and guilt – rarely discussed and tucked away from social lives, workplaces, and online presences. Stigma may lead to further suffering and isolation around “chosen” losses. Some family members judged me for what they saw as an act of betrayal and abandonment, simply “running away” from the problem.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Dr Gabor Maté, author of In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, shares an observation that guilt is healthier than resentment. Yes, I had begun to resent the fact that my dad’s drinking was ruining our lives.

Yes, I felt guilty for distancing myself after everything that he had done for me. I had to remind myself that my attempts to “fix” him had been futile. Ultimately I was devastated to lose the dad I loved so much, and grieved him long before he died, but I did not want to die with him.

There is a growing understanding of what family dysfunction looks like – and of the reality that we are allowed to cut off contact even if we are hardwired to love our family.

This is in contrast with traditional ideas of obligations despite the harm that dysfunction can cause. I am now a parent, and I hope my child will grow up to prioritise healthy, happy relationships.

Estrangement brings a very real loss, but it can also be a way to regain a life well worth living. I suspect that my dad would be proud of the strength and courage it took to get me here. Here’s to everyone navigating tough situations and opting to be well. I see you. You are not alone.

Long Going by Sophie Calon is out now (Honno, £12.99). You can buy it from the Big Issue shop on bookshop.org, which helps to support Big Issue and independent bookshops.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? Get in touch and tell us more.

It’s helping people with disabilities.

It’s creating safer living conditions for renters.

It’s getting answers for the most vulnerable.

Big Issue brings you trustworthy journalism that drives real change.

If this article gave you something to think about, help us keep doing this work from £5 a month.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty