“Spirit of Stalin, come and talk to me.” If you want to communicate through a medium with the Soviet Union’s feared dictator, Joseph Stalin, you can find a site on the internet via Russian Google. The occult has been in fashion with Russians since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, no doubt a reaction against the boring Soviet insistence on scientific rationality. It may be that those who seek to talk to the ghosts of Stalin and other famous historical and cultural figures are more interested in entertainment than politics.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

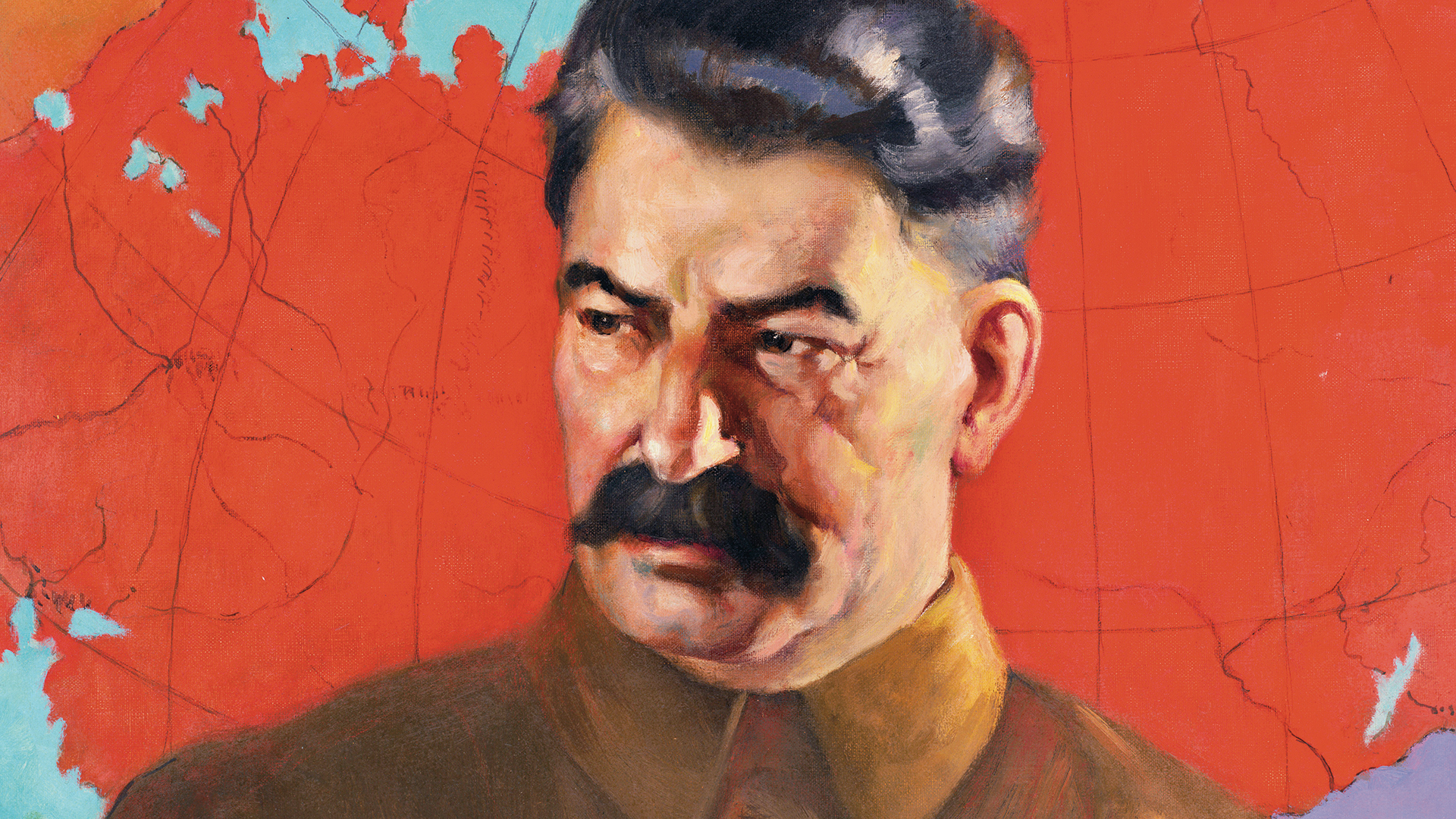

In Vladimir Putin’s Russia, Stalin, who ruled the Soviet Union from the end of the 1920s until his death in 1953, has been given a respected place in the history books, his achievements as a nation-builder outweighing the mass repressions that for many decades sullied his name. Although Stalin was ethnically Georgian, opinion polls show that a majority of Russians now consider him one of the greatest Russian leaders of all time, along with 18th-century nation builder Emperor Peter the Great.

But it’s been a bumpy road for Stalin’s reputation. On his 70th birthday, in 1949, Stalin was praised to the skies – lauded as a genius, father of his people, beloved teacher, and guide – both in the Soviet Union and by communists and other sympathisers throughout the world. He had led the Soviet Union to victory after four terrible years of struggle with Nazi Germany in the Second World War, in which at the lowest point 40% of the Soviet Union was under German occupation.

Stalin’s closest political associates, members of the Soviet Communist Party’s ruling Politburo, joined in and orchestrated the praise. They respected Stalin, but also had good reason to fear him, remembering the mass purges of the late 1930s and, more recently, the anti-western and antisemitic campaigns of the postwar years, which carried veiled threats to themselves.

Stalin’s death in 1953 was treated as a tragedy by the Soviet population. But it was probably a relief to his closest associates; and, as Armando Iannucci showed in his 2017 film The Death of Stalin (the same title as my book), there were elements of black comedy as well. Stalin lived alone since his wife’s death, shuttling between the Kremlin and his dacha on the outskirts of Moscow. Alone, that is, except for a small army of household servants and security guards.