Fog is a quiet kind of weather. It doesn’t beat down loudly on the roof like rain, or rattle the windows like wind. Fog won’t leave red marks on your skin like the sun, and you can’t mould it with your hands like snow. It is silent and unassuming, which is probably why we have not noticed that fog seems to be slipping away.

A 2009 study found that in Europe there had been a 50% drop in ‘low-visibility’ events (fog, mist and haze) since the 1970s, and around the world coastal fog is declining – which many scientists believe to be a direct result of climate change. In areas such as California, this reduction of fog – with the resultant heat and loss of moisture – could have disastrous consequences for ecology, and for the human population.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

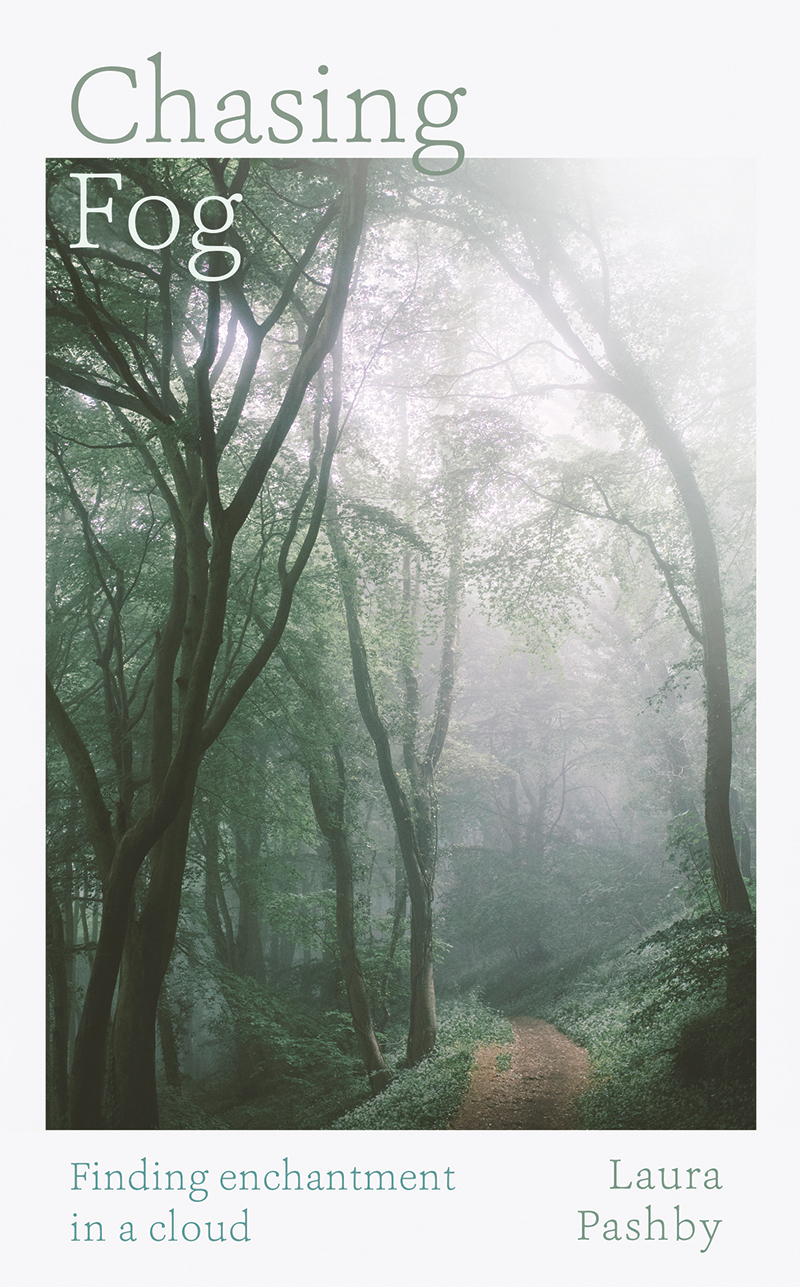

We see fog as something that floats over the surface – drifting by and passing through – but its tendrils are tightly plaited through the layered landscape. When fog inhabits a place, it leaves behind an indefinable trace – a feather-light memory of cloud’s quietly reverberating touch. Fog is captured by moisture-loving lichen and moss, living on in fragments of forgotten temperate rainforest that can be found in foggy locations such as Eryri and Cork.

The uncanniness of this eerie weather condition is woven into the folklore of our once misty isles. On Dartmoor, to be caught in the fog is known as being ‘pixie-led’. It was believed that pixies could conjure a fog to deliberately disorientate walkers, as could a local witch called Vixiana, who would summon a thick fog and lure travellers off the path in order to perish in a bog.

In Meirionnydd, Wales, the mountain Cadair Idris was said to be the domain of a dark and malicious king of the mist called the Brenin Llwyd. People, especially children, who strayed too high onto the slopes risked being snatched away by this terrifying individual, who approached the unwary in stealthy silence. The folklore of the East Anglian Fens tells of the ‘mist-whisperer’ Tiddy Mun, a strange creature, small as a child with long white hair and beard. He wore a pale-grey gown that blended with the evening mist, lived in the depths of the marsh waterholes, and protected his foggy fenland home by cursing those who threatened it.