Accordingly, in the summer of 1945 there was feverish speculation as to what had ‘really’ happened during those final days of the Second World War. Rumoured sightings of Hitler, alive and well, flooded across Europe, and then evolved into tales of an escape to a South American hideaway. Asked in parliament as to whether the government was satisfied “beyond all shadow of doubt” that Hitler was truly dead, even Winston Churchill had to concede he had no deeper knowledge than anyone else.

But the wartime Allies recognised that the idea of a still-breathing Hitler could fan the flames of Nazism. Determined to stamp out that abhorrent ideology, a series of intelligence inquiries were conducted into the dictator’s last movements. British and American investigators interrogated members of Hitler’s entourage; the Soviets scoured the bunker for clues.

Yet a climate of mutual mistrust amid emerging Cold War tensions precluded any open and honest exchange of information. It was not until 2018 that French scientists were able to affirm that dental remains, now held in Russian archives, had, indeed, belonged to the Nazi leader.

Read more:

An unconventional death scene and a belated ability to put the historical records in order thus offer two explanations as to why Hitler’s death has been so protracted. But we also need to consider the emotional investment of ordinary people.

Throughout WWII, the demise of Hitler was held up as a veritable war goal for the Allies. Propaganda posters depicted him battered and bleeding under the force of Allied military might. Wartime songs dreamed of dancing around Hitler’s grave and, more than once, premature reports of Hitler’s death resulted in the jamming of switchboards as people scrambled for confirmation of this much-desired news.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Several fundraising campaigns for the armed forces were predicated on selling nails for Hitler’s coffin, and there were recurring jokes and news stories about how people were planning to mark his funeral. Anticipating Hitler’s death became a useful morale booster and a popular form of wartime entertainment.

Such activities left people expecting a spectacular, fitting and, above all, public fall for the Nazi leader. Hitler’s death was held up as a symbolic endpoint to an era of conflict, terror and unimaginable atrocities. When that moment finally arrived – unwitnessed, unceremonious and devoid of justice – it felt strangely hollow.

Small wonder, then, that audiences felt compelled to reinvent the historical circumstances of Hitler’s death to craft a more satisfying outcome.

All too often, literature on Hitler’s death has become fixated on simply proving, or refuting, his suicide. But it is only by tracing the political and emotional meanings attached to his demise that we can fully understand the peculiar cultural resonance that his fate has engendered.

The Nazi dictator has taken a long time to die, precisely because the manner of his passing didn’t deliver the closure the world had been primed to expect.

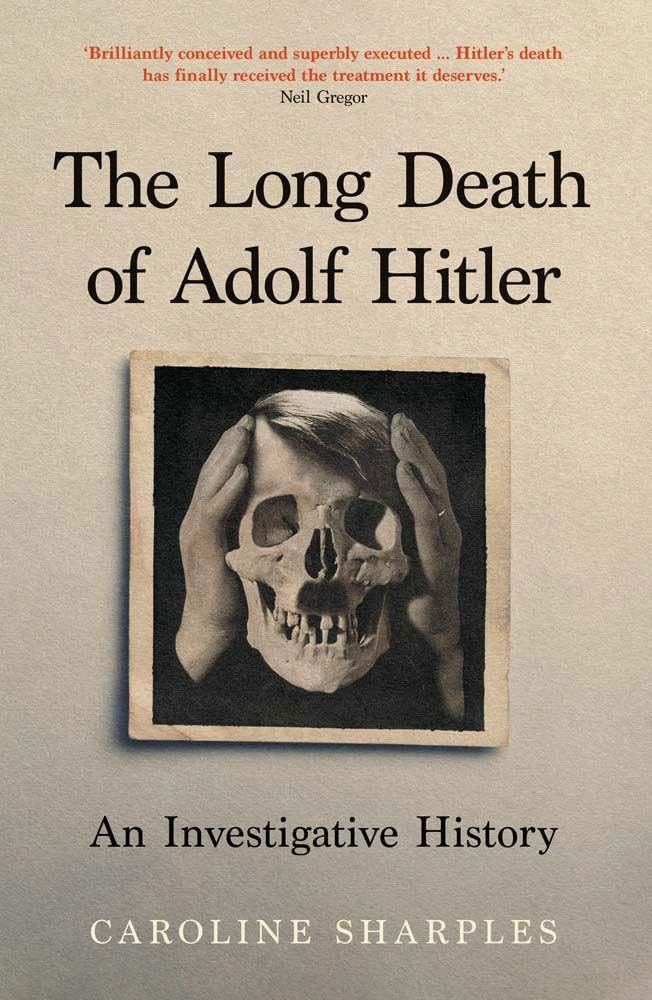

The Long Death of Adolf Hitler: An Investigative History by Caroline Sharples, is out 10 March (Yale University Press, £25). You can buy it from the Big Issue shop on bookshop.org, which helps to support Big Issue and independent bookshops.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? Get in touch and tell us more.

Change a vendor’s life this winter.

Buy from your local Big Issue vendor every week – and always take the magazine. It’s how vendors earn with dignity and how we fund our work to end poverty.

You can also support online with a vendor support kit or a magazine subscription. Thank you for standing with Big Issue vendors.