It’s a strange thing to admit, but sometimes I look at my daughter and I think to myself: “I have known her in almost precise proportion to the time in which David Bowie, the greatest pop star that ever walked the Earth, has ceased living.” It’s a shame that they just missed one another.

Yet, superstitious as I am occasionally prone to be, I like to believe that circumstances and timing mean they are somehow forever cosmically linked. At least in my mind. My daughter’s getting really into music now, and sometimes I’ll play her a bit of Aladdin Sane or Heroes and attempt to explain this wholly unscientific theory of mine. I’m proud to say that she is having absolutely none of it and gives me strong “What the hell are you on about, Dad?” face.

Read more:

Prior to his death, I can’t even claim to have been the most avowed Bowie superfan. I had many of his albums, and I had come agonisingly close to seeing him live (at the T in the Park festival in 2004, before he pulled out due to illness). But I’d never truly put in the work, and for that I felt guilty, as well as sad, when he left us.

Ever since, I’ve resolved to spend more time listening and reading and writing about Bowie. I enjoy soaking up all the good new radio and TV documentaries and magazine articles that come around every January, anniversary of both his birthday and his death (two days apart). The recent landmark 10th anniversary of Bowie’s passing has proved particularly content rich.

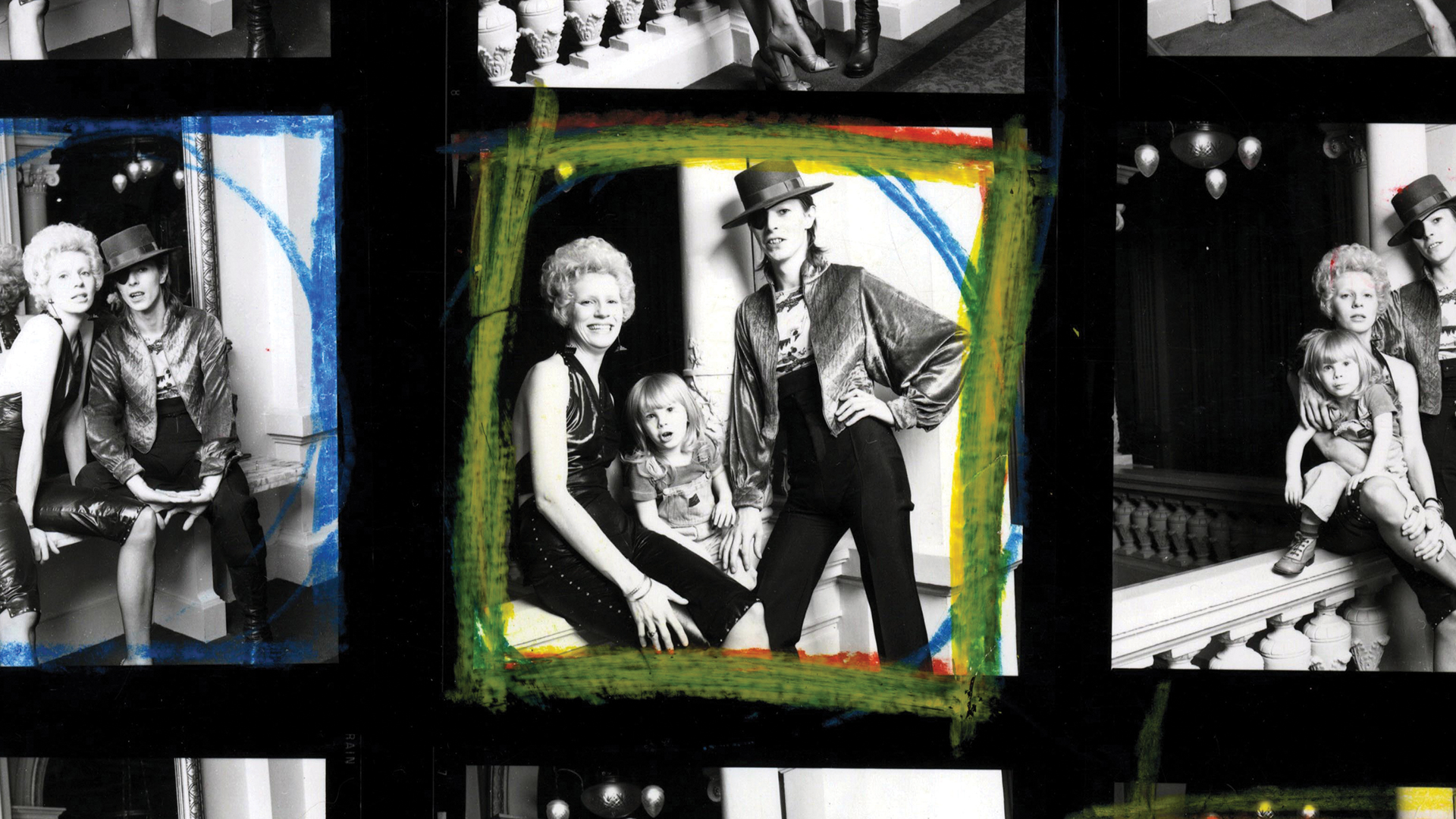

I find special fascination in learning about his journey as a father. How he eventually made up for lost time with his son, the filmmaker Duncan Jones, after being absent for much of his youth at the peak of his fame and in the pits of his decadence. How he contrastingly strived from day one to be the most regular, down-to-earth dad he possibly could to his much younger daughter Lexi Jones, eschewing touring and the limelight in favour of doing the school runs and making the dinner.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

He clearly found much quiet contentment in his family in the latter chapters of his life and career. I love how the wholesomeness and ordinariness of it all juxtaposes so sharply with the sex, drugs and oddness of his earlier days.

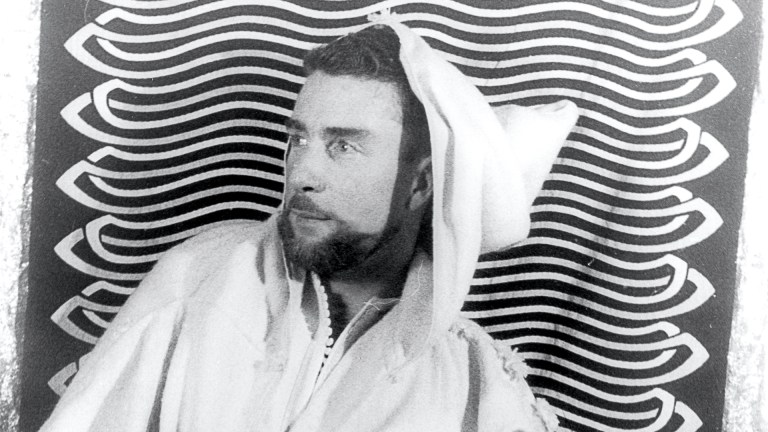

In his remarkable book Ziggyology: A Brief History of Ziggy Stardust, Simon Goddard weaves a knowingly absurd tale of how humankind dragged itself out of the primordial ooze precisely so that billions of years later Bowie’s Martian rock god alter-ego might one day stand on stage at the Hammersmith Apollo in London and break teenage hearts by announcing his shock demise.

It was a feat of fame and illusion that exploded the drab grey world of the 1970s into glorious futuristic technicolour.

A madly over-the-top way, I think, of making some sublime points. About how life is a miracle. And how we don’t get to share time on this planet with all that many people in the grand scheme of things – be they shapeshifting art pop geniuses from Mars, or our own kids.

The people we give life to, and the people whose art helps make us feel alive. We can be very grateful for them all.

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? Get in touch and tell us more.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Reader-funded since 1991 – Big Issue brings you trustworthy journalism that drives real change.

Every day, our journalists dig deeper, speaking up for those society overlooks.

Could you help us keep doing this vital work? Support our journalism from £5 a month.