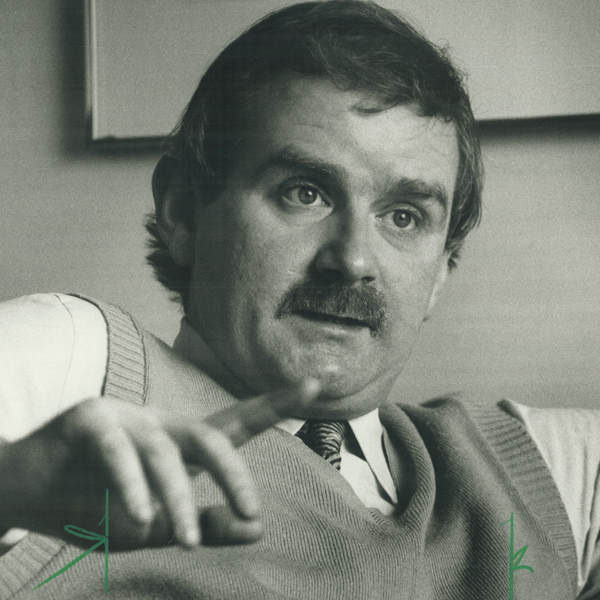

Acclaimed novelist and biographer Peter Ackroyd is known for his wealth of books tackling the history and culture of his native London and taking on biographies of historic luminaries including William Blake, Charles Dickens and Charlie Chaplin.

Here, in his Letter to My Younger Self, he explains why he would never dream of giving young Peter advice, why he considers being homosexual to be a blessing and why he’s always had “monkish inclinations”.

I was born in Paddington Hospital on October 5, 1949 and was then brought up on a council estate in West London which was, as far as I knew, the extent of the world. In retrospect it might seem a cramped or poor existence, but at the time it was all that I needed. You do not need to live in a great house, or in middle-class comfort, to entertain great thoughts. There were gangs of boys on the estate, but I never joined any of them. I preferred my own company, and that is a principle I have maintained. I have never joined a group or gang, whether of protesters, of letter signatories, of writers – because I was acutely aware that I might lose my individuality. It was an instinct.

I was brought up by two women – my mother and my grandmother – but I doubt that I ever realised how extraordinary they were. My grandmother was alert, ever curious and quick-thinking. My mother was highly intelligent, sociable and with a good-natured liberality that allowed me to develop as I thought best at the time. I could not have managed life without them, and now belatedly I register my gratitude to them.

As well as the women who raised me, my early life was influenced by religion and particularly of Roman Catholic piety. I became an altar server in our local Catholic church, and I believe that this had a profound effect upon me. It gave me a powerful sense of formal order and ritual as well as an inherent interest in the supernatural. That has prevented me from the excesses of empiricism or scientism, in the sure knowledge that the world (and indeed the universe) has a spiritual as well as material existence. In my early youth I also believed in a guardian angel who would protect me from serious harm, and no doubt this belief may still flicker out in moments of crisis.

When I was very young I wanted either to be Pope or a solitary monk like a Carthusian or a Trappist; the papacy was unfortunately out of reach, but I believe that I still have monkish inclinations. I like solitude and silence, to the extent that some people believe me to be a ‘recluse’. But this is not really correct. It is only the case that work has taken the place of prayer.