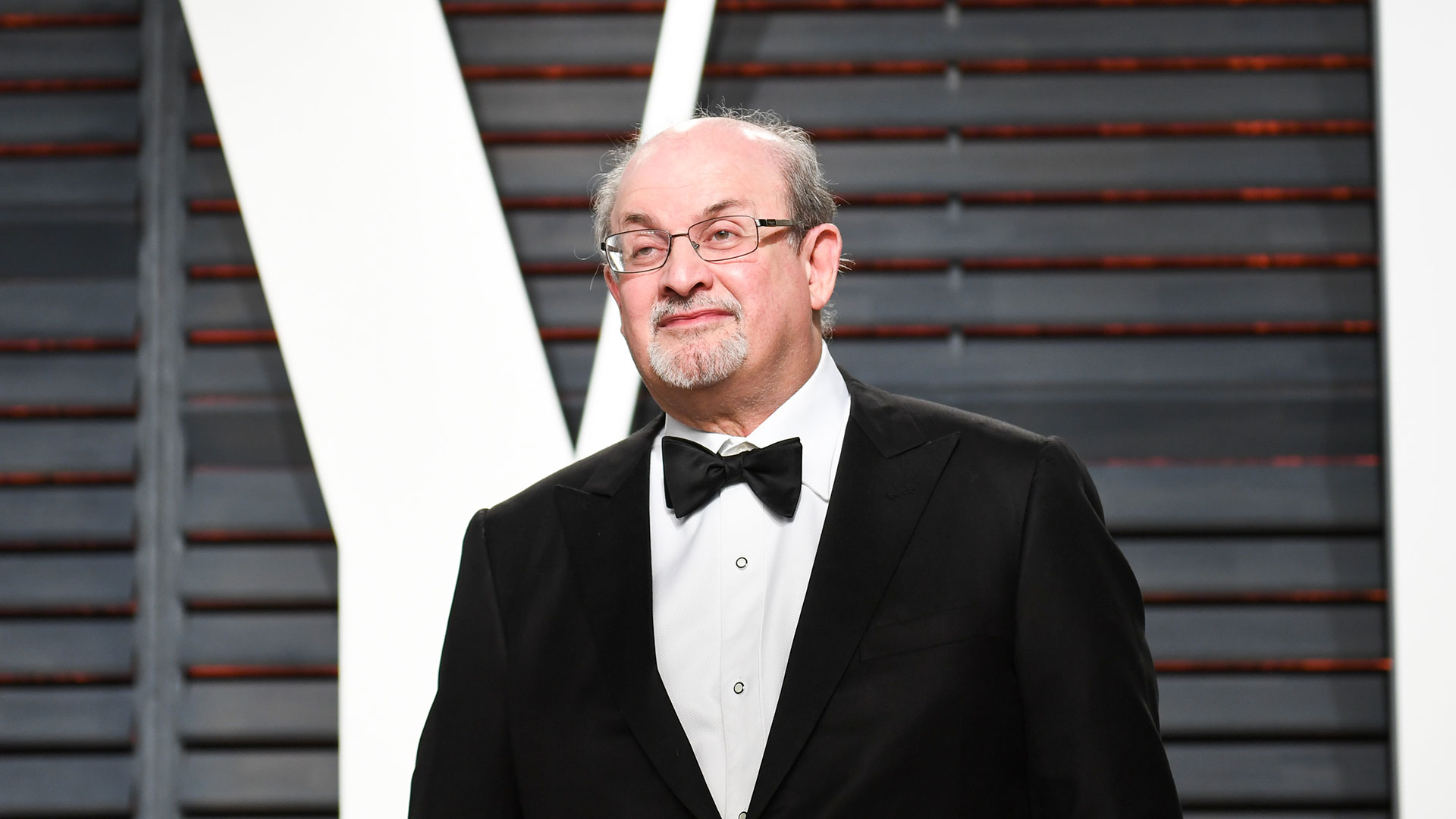

A version of this interview with Salman Rushdie was first published in The Big Issue in May 2016. In the wake of the shocking attack on the author in Chautauqua, New York, we decided to revisit his words and carry some that appeared in our Letter To My Younger Self book.

Rushdie explained how proud he is of his 1988 novel The Satanic Verses. Its publication, famously, led to the Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini issuing a fatwa, putting a bounty on his head and forcing him into years of hiding. Only in recent times had Rushdie finally been enjoying a level of freedom. And then the New York state attack happened…

I came from India to (boarding school) Rugby in England when I was 13. I had no idea that I would be judged as someone who was different to the others because I wasn’t English white. It really was a harsh awakening. It gave me a difficult time in this early years, I was quite unhappy. I was a pretty conventional public school conservative. That reflected my experience; I came from a fairly conservative, well off Indian family. and I’d been put into a school with boys from similar families from other places. I was a conformist at school, a good boy. I guess I did my rebelling later on.

I was very worried when I went to university in England that it would be a continuation of the same racist treatment. But my father convinced me it was a very good thing to go to Cambridge. Now I’m glad he did – it turned out to be a very happy time and undid a lot of the damage of school. I went to Cambridge in the mid 60s, when it was at the epicentre of that decade’s social change. It was a very good time to be 18 to 21. They were very political years, the period of protest against the Vietnam war. That was a political awakening for me. It was also the age of the counterculture. Someone called it the youthquake – young people were having an influence on society for the first time. Being part of that made me see everything – myself, my generation, the sexes, society – in a different way.

My family wasn’t religious at all – my father was always a non-believer and the level of religion my mother had stretched as far as not wanting us to eat pig. It seems strange now that religion has returned to the centre of the stage. In those days, in both England and Bombay, it just didn’t come up, it wasn’t a big thing. I did like the stories though – Islam has some good ones, though I think the Old Testament has the best. And it has more stories. At Cambridge I did a paper on the life of the prophet Mohammad and the early history of Islam. It was when I was studying for that that I came across the story about the so-called Satanic Verses. I remember thinking, hey; good story. Twenty years later I found out how good a story it was.

I didn’t see it then but now I recognise how much of the way I see the world came from my father. His interests have become my interests. If I could get back some of the time when my father was still alive I’d like to talk to him about now much his ideas came to influence mine, and express my gratitude. I was very close to both my parents when I was growing up. But my father developed a bad drinking problem and that created a difficulty in our family. And I was the eldest and felt it very keenly, so our relationship became quite estranged during my school years. It went on being quite difficult for many many years until we mended fences when I was much older.