Nineteen-year-old Mavis Trout arrived in Southampton from Jamaica in 1955 with little idea of what to expect. She had left her infant son Keith and his his father Elias Cunningham behind in Kingston to try and make a go of it in England where she had an aunt living in London who could help her out.

During the crossing she learned she was pregnant with another child. The baby, a boy, arrived the following spring on March 8 1956 at Whittington Hospital in Archway and was named Laurence, after her father. Two years later Elias brought Keith over with him and the family were fully reunited when the couple married in 1958. In the next decade the surrounding area especially Finsbury Park and Tottenham became the heart of the black community in north London and the Cunningham family, who moved several times over the years, remained in its close knit streets.

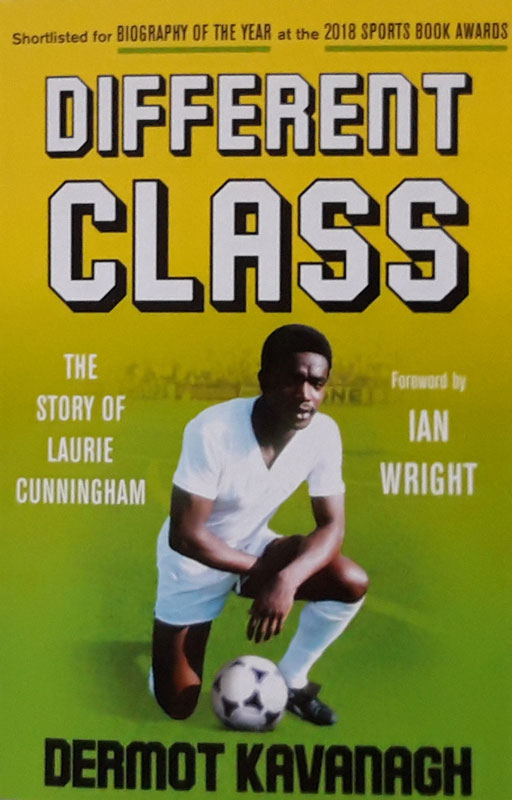

He was the first black player to represent England professionally at any level

Laurie Cunningham grew up to become a pioneering black British footballer. He was the first black player to represent England professionally at any level when he played for the under-21’s against Scotland in April 1977 where he scored the winning goal. He was also part of the glamorous trio of black footballers at West Bromwich Albion nicknamed the ‘Three Degrees’ who electrified the First Division with their buccaneering performances at a time of racial prejudice, when chanting bigots filled terraces across the country, and many managements considered black players to be cowards who were no good in the mud and lacked stamina.

Cunningham grew up in Finsbury Park, a poor area of London with derelict housing and bomb damage still visible from the War. Softly spoken and introverted as a young boy he was a natural when it came to any sporting activities. He loved to draw and paint and taught himself to play the piano at an early age. But most of all he loved to dance.

The Cunningham brothers had very different temperaments. Keith was quick to anger with a rebellious streak that got him expelled from primary school. He naturally looked out for his younger brother, in one incident when they were playing football in the grounds of a white council estate they were chased through the streets by a group of boys. Arriving home breathless their father asked what was up and when Keith explained he insisted he go back outside and fight the ringleader. Like many second generation children Keith had spent his early years in the Caribbean, and as he grew identified strongly with the simple and powerful message of Rastafarianism, whereas Laurie, who never visited Jamaica, was more immersed in British culture through his involvement in football. Elias teasingly referred to him as his “English boy”.