When Baz Luhrmann, Hollywood’s most irrepressibly over-the-top director, turned his eye to F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby in 2013, it ought to have been the perfect fit. Who better after all to adapt the empty decadence of the Roaring Twenties than a man who built his career on the potency of a gilded image, on how solid gold idols can disguise nothing more than gold leaf and a rotten core.

Yet the resulting film aligned more with Jay Gatsby’s self-delusion than Fitzgerald’s prophetic, pre-Depression era vision. “They were careless people,” Fitzgerald warned of his characters; but Luhrmann’s film – its delicious design and starry-eyed ascription to the bruised romanticism of failed dreams – cared too much, believed too much in its own false god.

Luhrmann has always been a director obsessed by the thematic and narrative possibilities of aesthetic: sometimes it works, as with Romeo + Juliet, where sticky California heat and pimped-up guns become a cipher for unchecked desire and rage; sometimes, as with The Great Gatsby, the aesthetic takes over, layers of glitz painted so thick as to obscure the hollow centre beneath.

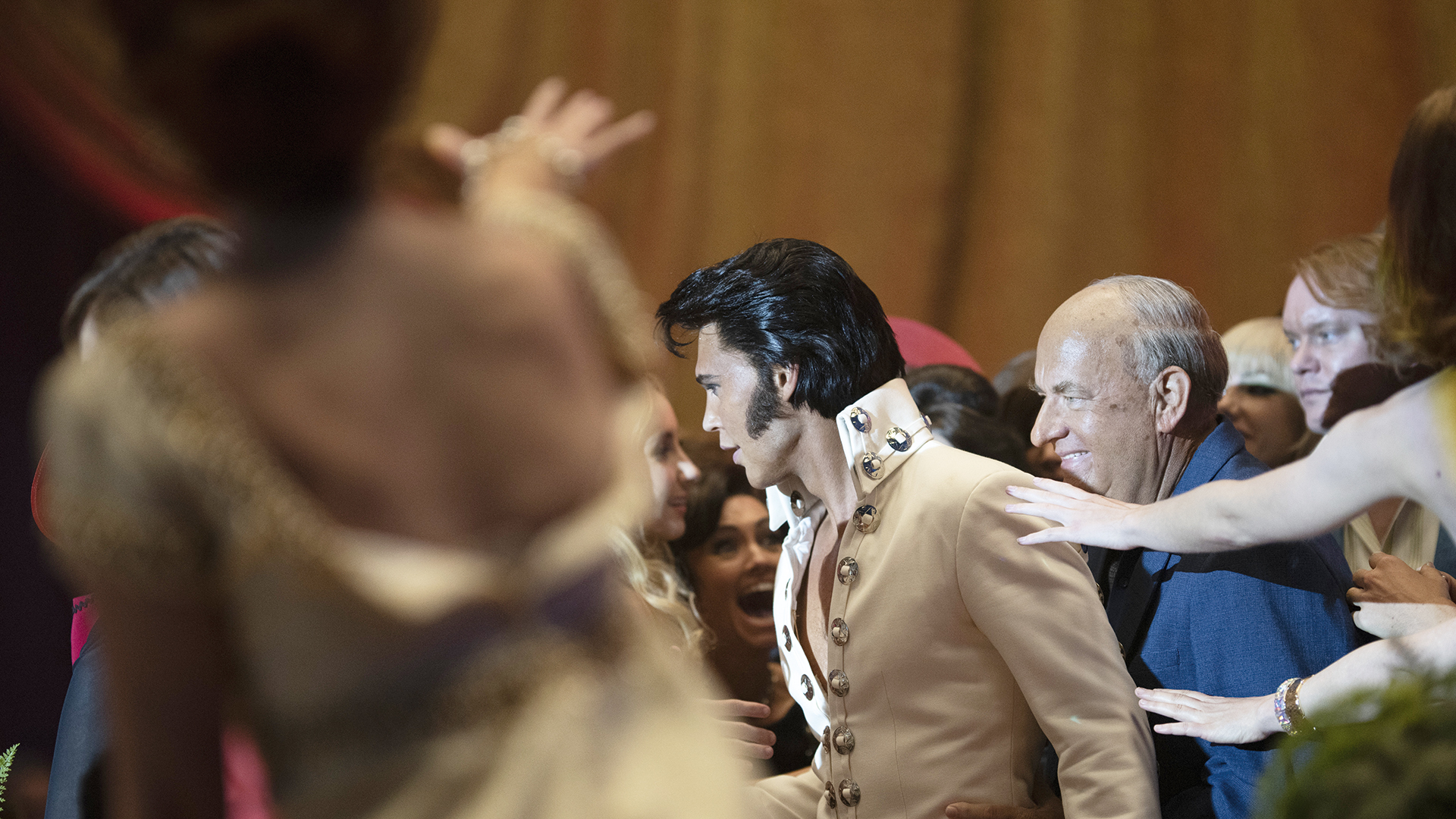

Elvis, Luhrmann’s biopic of the king of rock’n’roll starring newcomer Austin Butler, trades in many of Fitzgerald’s concerns: the fragility of the American Dream, the mythology of wealth and glamour, the political possibility of image making. Yet unlike Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby, Elvis is fascinated not just by the visual potency of an image but by its aftershocks: the cultural legacies it carves out for both viewer and creator.

“The image is one thing and the human being another,” Elvis Presley once said. “It’s very hard to live up to an image.” Yet his life was largely steered by the former. His rise to fame was framed not just by the rise of the American teenager and its rebellious slicker aesthetic, but also by his deliberate intersection with Black culture in a time of brutal segregation, his wanton sexual magnetism in a time of intense female repression.

At two hours and 40 minutes, Elvis has all the bagginess of a by-the-book biopic, but it is in the moments where Luhrmann homes in on the political nature of Presley’s aesthetic persona that it finds its (gyrating) groove.