I didn’t want to define what he did but I hoped that anybody could associate with him

“I had young children at that point so I knew the series, I was the mother they watched with,” McKee recalls. “I showed Mr Benn to the BBC lady – she was very nice – and she said that’s great, this could be just the thing. It was all very casual.

“Nobody works like that now. It’s always a committee and everybody has to say something, which probably produces a more polished effect but you lose that individual voice. They had it right back then. Mr Benn was really very amateurish but full of enthusiasm.”

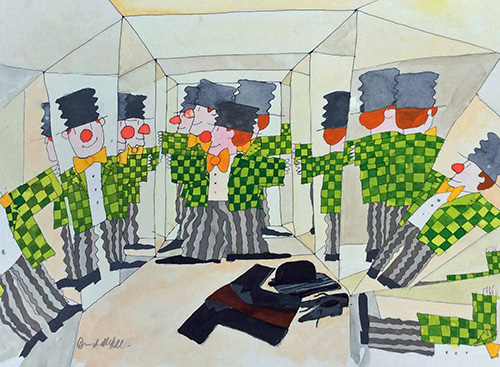

Each episode of Mr Benn would find the businessman ambling to his local costume shop. After changing into fancy dress, be it a knight, clown, cowboy, spaceman or pirate, a door would appear that wasn’t there before and walking through it transported Mr Benn into that world. His adventures generally involved a bit of problem-solving and helping others.

Ray Brooks, who delivered the cosy voiceover on Mr Benn, says the secret of his success is straight-forward: “Grandmas come up to me and say their grandchildren are fed up with today’s cartoons but they love the simplicity of Mr Benn, the fact that he’s very moral, always sorting out people’s problems – including dragons.”

A morality runs through all of McKee’s books, especially the Elmer stories that have issues about acceptance, equality and understanding at their heart. Elmer has been hailed by The Guardian as a LGBT hero, the multi-coloured

elephant “opening people’s minds to accepting difference and being

themselves for a quarter of a century”.

“It’s nice when stories have a reason for being,” McKee says. “When I was young I loved Aesop’s Fables, and the parables in the Bible at school. I liked the fact I could see a different meaning in the story. As I grew older, I often saw a different meaning than I did when I was young.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“I was probably brought up – well, there’s no probably about it – I was brought up in a moral tradition, and that became natural to write. Even if there’s not an obvious moral in the story, there’s often a moral feeling. There’s usually a subject that needs to be talked about. The book may not say a lot about it but it does give a way into talking about the subject.”

In Elmer and the Hippos, published in 2003, the elephants are outraged when a group of hippopotamuses come to live in their river. In 32 pages, the book outlines simply and concisely issues and solutions to the migrant crisis. And this is a picture book for kids, remember.

“I’ve always thought you can’t say to people, you can’t come here,” McKee explains. “They are going through hell. Their friends are at home, everything is at home, that’s where they want to bring their children up. They want to say, when I was young I used to throw stones in this river, come and throw stones with me. They don’t want to be getting into a rubber boat risking their lives going somewhere they don’t speak the language.

“In this case the hippos needed water. If there are problems, it’s those we should be looking at. You can’t just say no, you have to get involved and help.”

[Refugees] are going through hell. You can’t just say no, you have to get involved and help

When problems are reduced to an elemental level, right and wrong become obvious. It’s something children innately understand even if the general public sometimes lose sight. “It often takes a child to explain to an adult what’s going on,” McKee points out. “Children generally seem to be both very open and pretty bright about the fairness of things.”

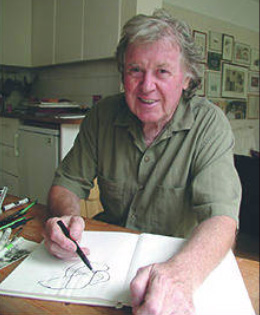

To celebrate Mr Benn’s 50th birthday an exhibition displaying artwork, including some rare archives from the TV series, is being held at The Illustration Cupboard gallery in London. Like Mr Benn, David McKee thinks we can all have our own adventure. All stories offer escapism.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“When I was young everybody seemed to tell stories,” McKee says. “My mum was a storyteller, my teacher at school told stories. The guy at Scouts would tell ghost stories about the area – Tavistock is a very ghost-ridden town. When my father came home on leave during the war he would recount things that happened but in a way that was a story. It was always fantastic.

“Eventually I started telling stories, first I told stories to myself, then when I was at college I’d tell stories to friends. People didn’t have stuff in their ears or telephones going all the time. Perhaps there’s more conversation in some ways today but a different kind of conversation.”

How can we learn to tell more stories to ourselves and each other?

“I think the air is full of stories. What people perhaps don’t have so much is the silence to let them enter and arrive. Find calm and peace when you’re completely relaxed.

I think the air is full of stories. What people perhaps don’t have so much is the silence to let them enter and arrive

“For me one of the great places for stories used to be the bath – these days I shower – but I would lie in the bath and there comes a moment when your body temperature and the water are very similar, your skin’s gone all crinkly because you’ve been in so long, and your body awareness disappears. That’s when stories come into the mind.

“I look out of the window now and it’s amazing. I know that emptiness is full of all the television programmes, all of the radio programmes you can think of, full of all the telephone conversations – it’s full of stories. If you tune in, you can receive.”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Celebrating 50 Years of Mr Benn with David McKee runs until September 16 at The Illustration Cupboard Gallery, London SW1Y. On August 23, McKee will be there to celebrate Mr Benn’s birthday. There will be tea and cake

All artwork by David McKee