I was born just before the Second World War broke out, and when it did I was swiftly evacuated to the English country town of Luton. This is where I developed and grew, away from the filthy, war–battered slums of Whitechapel where we were living. I swam daily in the open–air lido, collected conkers in autumn which shone like gems, and loved my country life.

When I was 10, I entered this fantastic world which was more bizarre than even Alice could have experienced in Wonderland. Mum had plans to join her brothers and sisters who had emigrated to New York, so we drove to Southampton. As I exited the car, I saw this gigantic grey wall. What was it? Some mysterious massive building? The penny dropped, it was a magnificent ship, the first Queen Elizabeth. I had never seen anything like it in my young life. This was the template against which any future experience would be measured. After five days of this magical journey, we docked in Manhattan at Pier 93. The skyscrapers were like hallucinogenic monsters to my young eyes and I stood on deck in the misty dawn totally hypnotised. I had reached the climax of my young life. I had arrived in paradise.

Everything intrigued me. And I seemed to intrigue everyone. They were fascinated by my accent. We were housed in a bit of a slum but it couldn’t have mattered a fig to me because I was in paradise. I went to PS70 – Public School 70 – and the curriculum was so behind the UK that I could catch up with the algebra and geometry, which had baffled me in England. Every morning we would gather in the auditorium and pledge allegiance to America, my new, adopted, wonderful world. I was in love with hot dogs, sauerkraut and mustard for 12 cents, my daily diet. But this idyll was to end after three months when my father gave up – he didn’t have the guts to go through with it in his middle age. So we had to return to the horror of bomb–blasted London.

It was 1947, the snow was thick on the ground, I had to share a bed with my cousin Barry. I fascinated my classmates at primary school, wearing the smart American suit my cousin bought me in New York while they were still wearing shabby short pants. They gave me the nickname Spiv. I sat the 11 Plus and won a scholarship to Raine’s Foundation Grammar School. I was recovering my pride in the smart uniform. I loved the school and the traditions but hated the corporal punishment for trivial misdemeanours like talking too much in class. I was given three hard strokes of the cane. No one had ever struck me before or inflicted such painful agony. I had three large red welts on my backside. From where I was in paradise, now I was in hell. From that day something changed in me. I began to hate authority with a venom, and that has never left me.

I had all these friends but they were all over 40. I was looking for a father figure

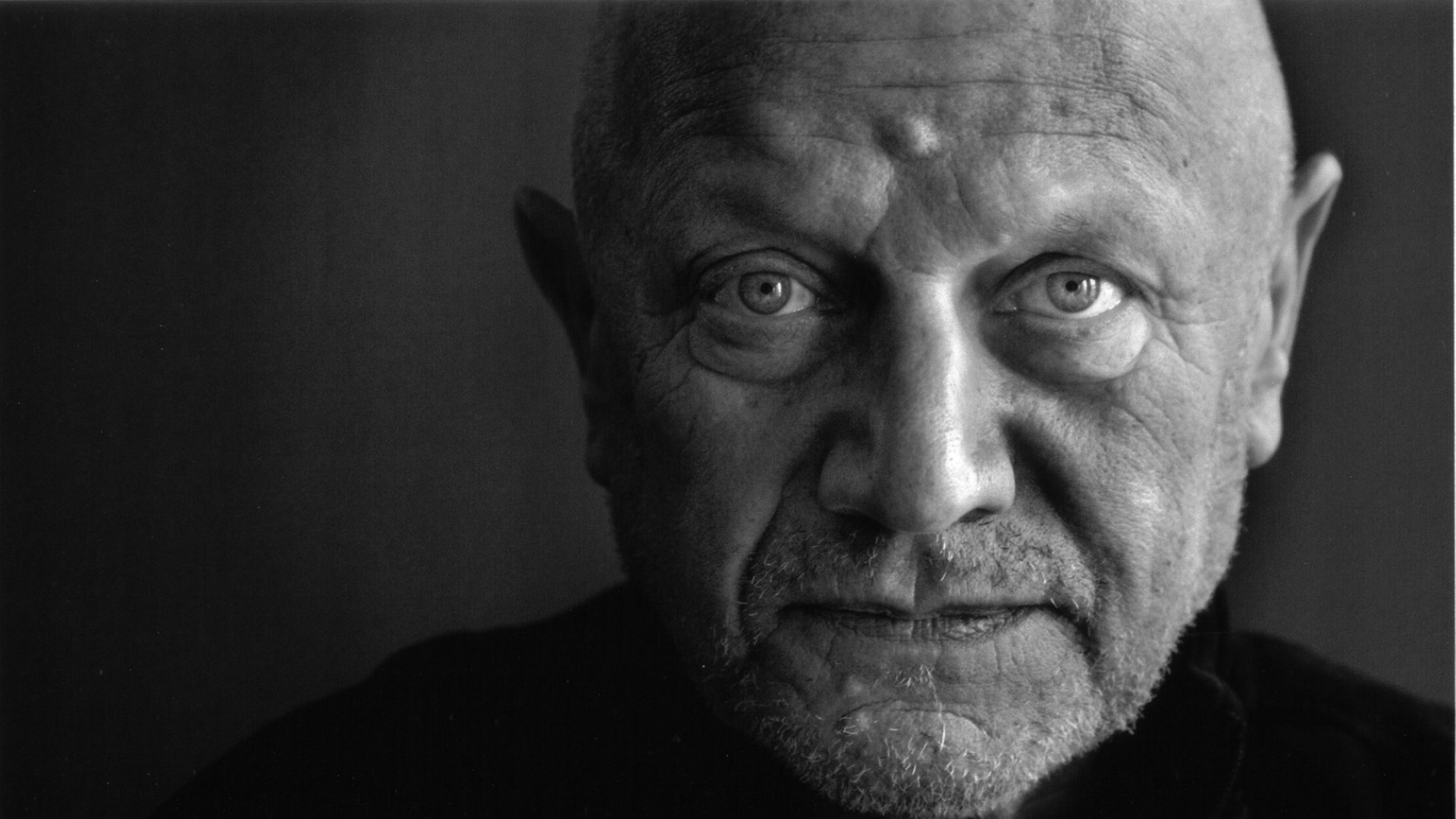

I knew at 14 that my destiny was to become an actor. But I had no idea of the routes into it. It wasn’t a working–class profession. But I had this fantasy. I wanted to be in the movies. I wanted to explore the world. I wanted to be an American – that was my obsession. I loved Marlon Brando. We had three cinemas nearby so I lived through the fantasy of that world. The movies was all we had. And since I knew I was going to be in the movies, I didn’t care what I did when I left school. I had ambition but no skill. I wanted something that would take me back to that feeling of euphoria I felt in America. So I had to do something that would enable me to be rich enough to buy a seat on a ship and go back to New York.

I had a run-in with the law because I had no values and no inspiration. Maybe my father didn’t have time because he was trying to make a living himself, but all I needed was someone to give me aspirational thinking. I left school before my 15th birthday and not one teacher at the second-rate slum of a school I had moved to – a second–rate dosshouse called Groves – asked what I would like to do. Nobody gave me a clue about anything, so I left school clueless and got in trouble. They put me in a juvenile home when I was 15. It was so awful. There were freezing showers in the punishment block, which of course they put me in. It was the nastiest place in the world. Eventually the government closed them down. They were too brutal.