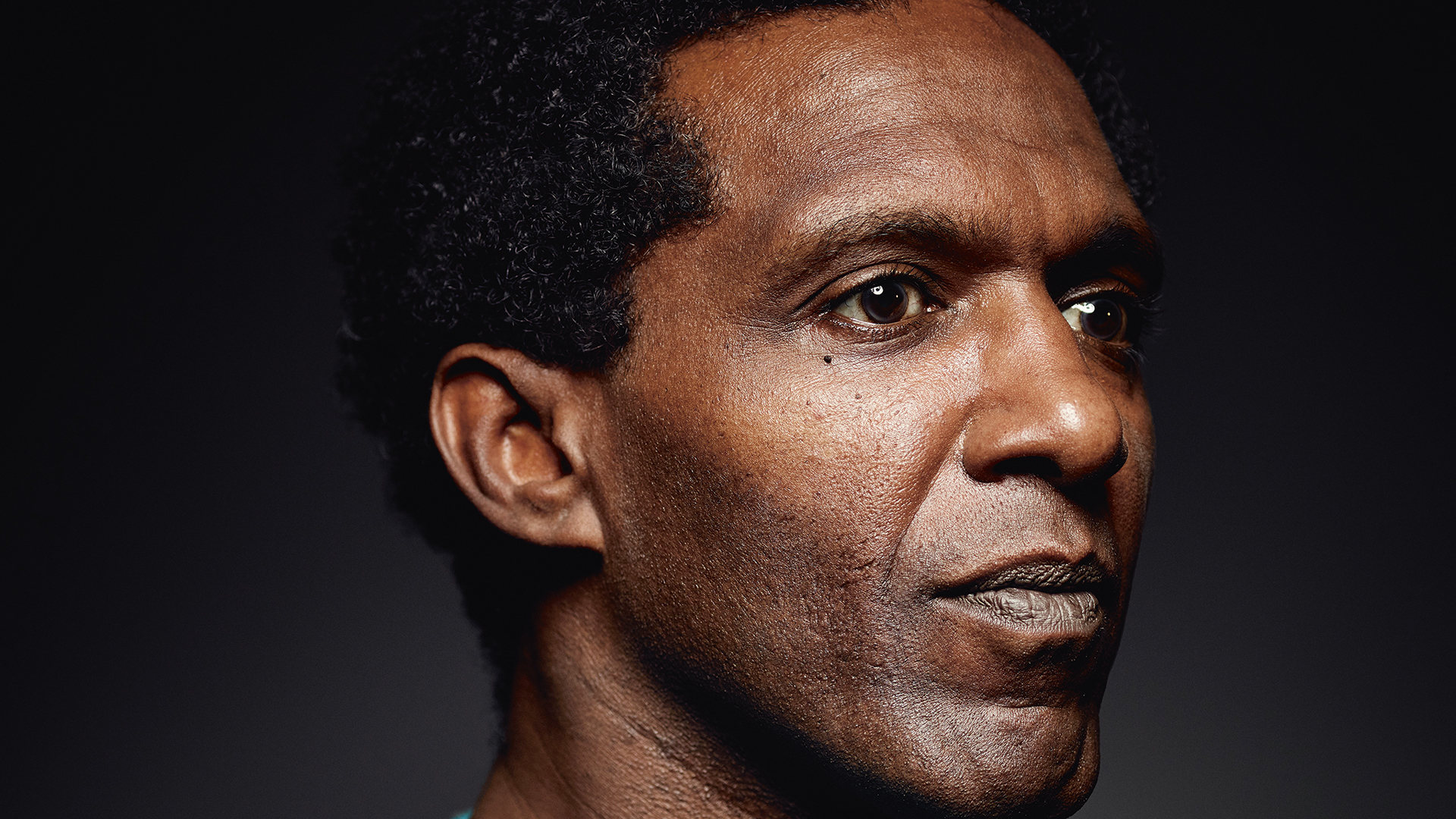

The memory of my younger self is something I struggle with. I have no one to dispute or agree on the memory of me, good or bad. I was a people-pleasing 12-year-old. My mission was to make you smile. It is clear now that I was like that because I didn’t know why my foster parents got rid of me aged 12. I assumed that everybody leaves. The central idea of relationships in my childhood was: people disappear. They blame you and you don’t know what you have done. My smile was to keep people there for as long as I could.

By the time I was 16, I was angry. I was imprisoned in Wood End assessment centre, my fourth and last children’s home. [Sissay’s Ethiopian mother had him fostered as an infant in what she thought would be a temporary arrangement while she finished her studies in the UK.] I didn’t know anybody who had known me for longer than a year. It was a different children’s home, with different staff members in it, with different children. In 1983, Margaret Thatcher was starting to take the north to pieces. I was brought up in Wigan, which has big resonances with George Orwell.

The assessment centre I was imprisoned in was very Orwellian – marched up and down long corridors, watched in the showers, strip searched if you had visitors. I had to suffer the abuses and not say anything. My capacity to function started to shut down. I couldn’t go outside, I couldn’t walk to the shops, the air outside felt like it had an ingredient of acid. It was illegal to imprison a child, but because I had no family they could put me in there knowing nobody would call. I would tell my younger self that he was right. He did not deserve what institutions were doing to him.

Aspirations are free – and they would not even give us them. I had no imagined future beyond leaving care. We were seen as problems to be solved, rather than opportunities for greatness. But any child is an opportunity for greatness. There is a lack of aspiration, so nobody tells kids in care to buy property. I bought my first property a month ago.

At 16 I got tuned into Bob Marley. I went deep. I had been into David Bowie at 15 – he was something else from somewhere else and so was I. But I was finding out about myself through reggae. I learnt about race through Bob Marley, but also through how I was treated. I became political from the moment I understood that race was central to what happened to me in the care system. I did poetry readings for the anti-apartheid movement. If you have suffered racism, a large part of your job is to stop other people from suffering it.

Said the heart to the head

Said the head to the heart

'We have more in Common

Than sets us apart' pic.twitter.com/n3wCiDh1l7— lemn sissay OBE FRSL (@lemnsissay) September 5, 2019