There’s a sense of reverence as Hamilton describes his parents’ garden. The row of pine trees along the bottom border, the chickweed that sprang up in the trench for his toy soldiers, the patch of nettles – this upbringing created a man in awe of the natural world.

The patch of nettles specifically marked Hamilton’s first attempt at foraging. “I can remember the nettles and I can remember the fact that it was a disaster.”

Hamilton explains that while nettles are delightful in a soup this time of year, once they grow “really tall” they lose their charm. “They’ve got a chemical in them that crystallises in the leaves and makes them taste a little bit like sand.”

Besides the nettle soup, there was also the time he ate a daffodil, which unbeknown to him at the start, are poisonous. These early missteps didn’t deter him though.

“Foraging is freedom to me,” he says. “I had lots of really bad jobs in my 20s and relied on other people for food. Now I know that I’ve got the capability to go out and pick some food and at least have a plate of food.”

But he knows foraging isn’t a quick fix for the cost of living crisis. He says that if he’d been told to go foraging when he was hungry, he’d have told the person to “fuck off”. Rather he says it’s a way to feel “fully human”.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“When you start to engage with the natural world with foraging, then you start to love it more. It’s a very different experience than getting something and shoving it in the microwave. It gives you an idea of the seasons. It gives you a complete idea of climate change. You know what the weather’s doing to our plants, it makes you very in touch with what’s happening in the world.”

It’s a movement that has mushroomed in popularity, in no small part due to lockdowns.

“When I first started teaching, it was the usual suspects. You could ask what everyone voted and they’d probably all say the Green Party. It was also all flowing robes and long hair – myself included.”

“There’s actually more of an abundance in a city than there is in the countryside because we’ve got loads of cultivated gardens, allotments, all that kind of stuff around. It’s about knowing where to look.”

To the sceptics, Hamilton smiles as he says, “Give it a go. You’ve probably already foraged. You’ve probably picked a blackberry. You probably know what nettles and dandelions look like.

“There are a lot of plants and a lot of knowledge you already have.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“Just ease yourself in gently, you know, one or two dishes, one or two little extras… You can use it to enhance what you’re already eating.”

So, with this in mind, I went back outside. It took more than 90 seconds, yet I did find an abundance of dandelion leaves. I came home and boiled my leaves for the recommended 20 minutes. Hamilton’s book suggested a lemon, olive oil and salt drizzle. The leafy greens reminded me of spinach. I dished them up in a bowl and didn’t like them at all.

But I did gain something from the experience. I engaged with my local environment, noticing things I hadn’t noticed before: the first of the magnolia blossoms, birds building their nests in the trees.

It was lovely to be in touch with my surroundings in a way that did feel fully human.

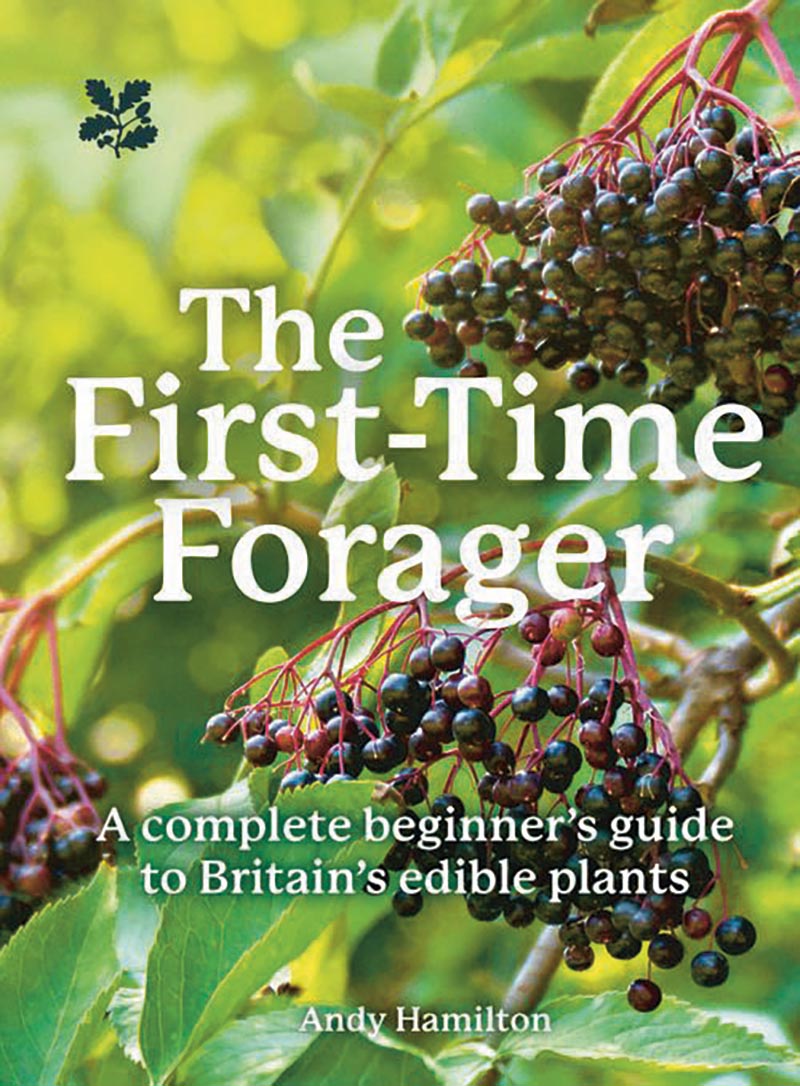

The First-Time Forager by Andy Hamilton is out now (National Trust Books, £12.99). You can buy it from The Big Issue shop on Bookshop.org, which helps to support The Big Issue and independent bookshops.

This article is taken from The Big Issue magazine, which exists to give homeless, long-term unemployed and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income. To support our work buy a copy!

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

If you cannot reach your local vendor, you can still click HERE to subscribe to The Big Issue today or give a gift subscription to a friend or family member. You can also purchase one-off issues from The Big Issue Shop or The Big Issue app, available now from the App Store or Google Play