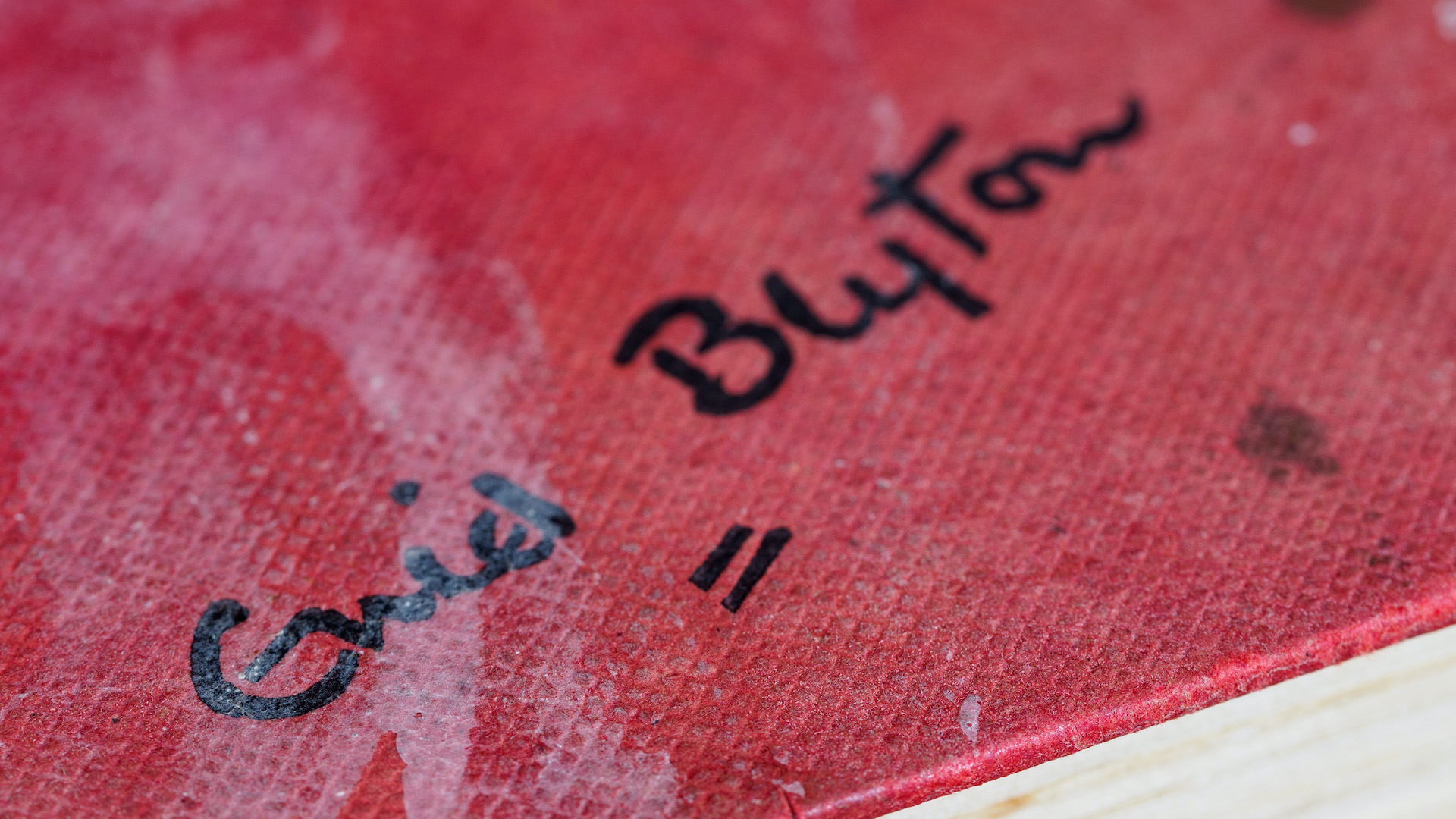

English Heritage, the charity which looks after sites and artefacts in the country across centuries, recently updated its website to acknowledge the “racism” and “xenophobia” present in Enid Blyton’s work. On the page dedicated to Blyton – voted Britain’s best-loved author in 2008 – the acknowledgement reads: “Blyton’s work has been criticised during her lifetime and after for its racism, xenophobia and lack of literary merit”. Visitors to Blyton’s blue plaque on her former home in Chessington will be served the same message when viewing it through the organisation’s app.

In response, some have lamented that the author has been “cancelled”. It is an increasingly common defence invoked against criticism in the face of modern values, but the truth is that English Heritage’s mere acknowledgement of Blyton’s racism is a small step towards Britain being open and honest about the prejudiced attitudes of some of its much-loved historical authors. Dismissing it as another “cancelling” obscures the slow progress being made and until real change is made to end power imbalances and inequalities in publishing, claims of being “cancelled” are little more than distractions from the problems we all have to face up to.

The update from English Heritage is not the first time that Blyton’s racist and xenophobic attitudes have been challenged. In 2019, plans for a commemorative 50p coin celebrating the author fell through as a result of her “racist, sexist and homophobic views”. Objections to her work extend as far back as 1960 when book publisher Macmillan rejected her story The Mystery That Never Was due to a “faint but unattractive touch of old-fashioned xenophobia”. But her sales have been relatively unaffected by such claims – in 2017, she was the UK’s 12th biggest-selling children’s author. So what does being “cancelled” actually mean?

The concept of separating the art from the artist has become a hot topic in recent years, driven in part by the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements. This encouraged wider debate about the art we consume and how we consume it, raising questions: can we enjoy art created by those accused of problematic behaviour, or art that contains its creators’ prejudiced attitudes?

When audiences began to express their disapproval of prejudiced work through boycotts and public criticism, it was branded “cancel culture”, and claims authors had been “cancelled” picked up speed across the publishing industry. J K Rowling claims she has been cancelled multiple times, and author Lionel Shriver has called “cancel culture” in publishing “a quasi-Soviet phenomenon”. Classic authors – such as Blyton, and those published throughout the 20th century and earlier – have also been in the firing line. Roald Dahl’s family apologised for the author’s antisemitic comments in 2020, a group of students at the University of Manchester replaced a Rudyard Kipling mural in 2018 in protest against the author’s racism, and Hergé’s Tintin in the Congo sparked a campaign to remove it from the children’s section of bookshops due to its “racial prejudice”.

To be “cancelled” is to have prejudiced opinions publicly called out – criticised – by audiences. This seems to be the greatest concern of those put under scrutiny. Acknowledging prejudiced attitudes in the works of authors is often dismissed as political correctness gone mad.