Mulled wine season is upon us, and you’ll find few complainants that the warming glühwein at one of the many Christmas markets is not the truest reflection of the grape and the place it was grown. But tinkering with fermented grape juice has been the source of battles and riots over the course of history.

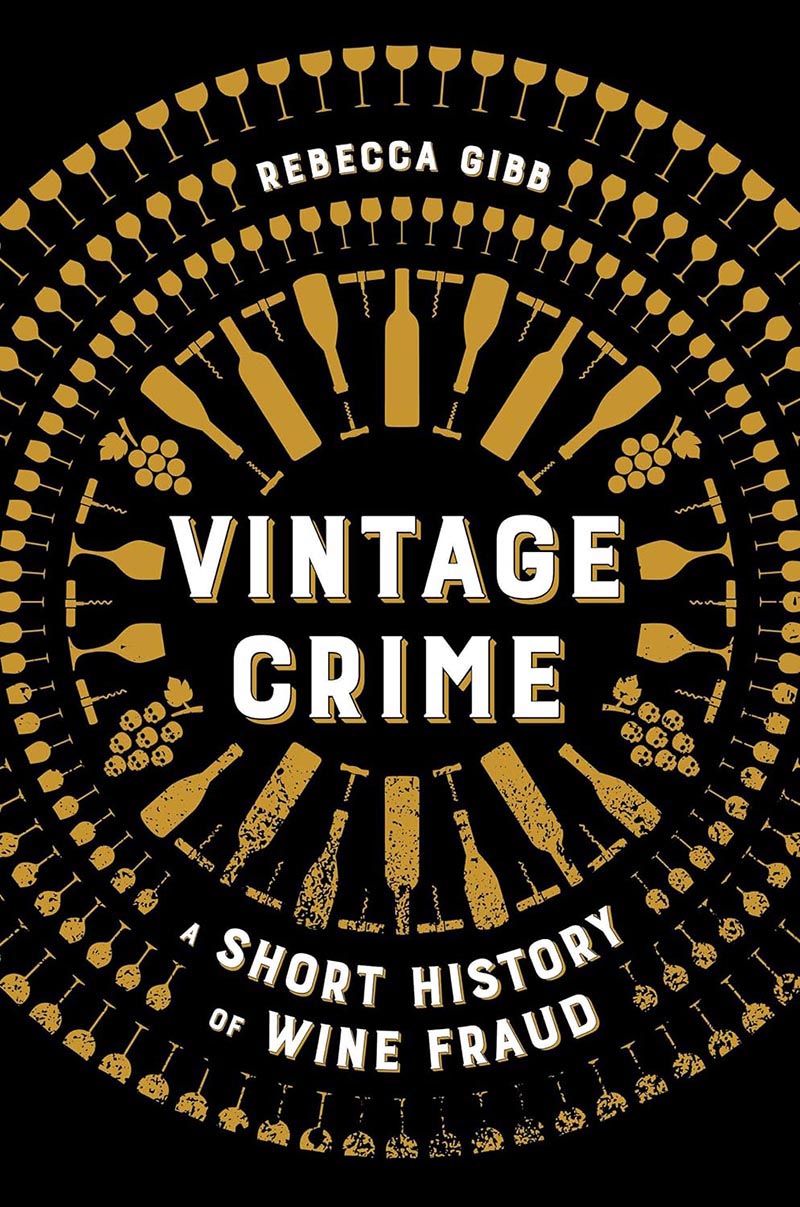

Deception has coursed the underbelly of the wine world for millennia. In 1852 a select committee in London’s House of Commons lamented the state of play: “The wine trade itself is much altered from the respectable character it used to bear; persons of inferior moral temperament have entered into it and tricks are played, which in former times would not have been countenanced. The trade is getting a bad name.”

Change a Big Issue vendor’s life this Christmas by purchasing a Winter Support Kit. You’ll receive four copies of the magazine and create a brighter future for our vendors through Christmas and beyond

The committee had clearly not done their history homework: meddling with wine is as old as the vine. Wine has been spiced and seasoned since Roman times: herbs were commonly added including fennel, pepper or cumin to pep up a wine. The end goal was to make wine more palatable rather than deliberately deceive the end consumer. The drinker was often grateful to the maker for masking the taste of the wine, which would quickly turn sour without any of the technologies that modern winemakers take for granted.

In the first century AD, Pliny the Elder recorded the many forms of adulteration taking place: from herbs and seawater to honey and pounded marble, the list of additives was extensive and, they weren’t all conducive to healthy living, particularly a lead-riddled syrupy mixture which could poison the regular drinker, leading to many health problems and sometimes death.

It is only very recently that wine has been able to survive long journeys without becoming undrinkable or age for than a year or two before turning to vinegar. Today, we are lucky that most wines – even those piled high and sold cheap in the next aisle to your box of cereal or packet of loo rolls – are generally free of faults and taste pretty good. Before high-tech wineries came along with laboratories and computerised tanks, and temperature-controlled shipping containers carried wines across vast oceans, quality was patchy.